Written by J.B. Shepard, a professional pet photographer and founder of the Puptrait Studio.

Photographing a running dog isn’t a simple task. In fact, taking great pictures of running dogs consistently can be down right difficult — as it requires a photographer to understand dog behaviors, how to use artificial light sources / light modifiers, how their camera functions in extreme conditions, and how to frame less than optimal scenes.

But with proper understanding of the hurdles specific to these pet action shots and equipped with a few simple techniques on how to best mitigate these technical pain points, even a beginner pet photographer can learn how to take beautiful action shots of their dog.

How do you photograph a running dog?

Photographing running dogs takes two things – patience and luck. That said, the better prepared you are for your dog’s action photoshoot and the more you practice, the luckier you will get. When working in less controlled environments, something will inevitably go wrong. But the 15 photo tips listed below should lend you the techniques, equipment, and mindset you need to mitigate more common technical hurdles, making it much easier to overcome the unexpected and prevent your session from going completely off the rails.

1) Safety first.

It’s important to scout locations prior to your shoot day. This might sound obvious, but this is something that pet photographers and dog owners take for granted all too often. You may have visited the location prior, you may even have taken your dog off leash at the spot previously. But conditions change.

Always check the weather prior to your session date. It’s always better to reschedule than risk injury or damage to gear. Also, be sure to double check that there are no other events scheduled for the location during your shoot date. A quick Google search looking up the date and name of the location can help you avoid unexpectedly walking into a farmers market, fun run, rally, wedding or other crowded event that might compromise safety or potentially distract your pup.

Keep it legal

Be sure to also check if there are any restrictions or permit requirements for shooting at the property. If you are planning on shooting at any National Park or National Monument in the United States, you will likely need to obtain a photography permit from the National Park Service or risk receiving a heavy fine.

Some locations may not allow photography at all, others may limit what gear you might be able to use. Not to mention that many municipalities and destinations have fairly strict and enforced leash laws. Ignorance is rarely an effective legal defense and is unlikely to get you out of having to pay for a citation. So, please do your self a favor and check statues and rules prior to your shoot date.

2) Give the dog room to run

We have photographed hundreds of dogs and we have never met a single pup that can jog in place. If you’re looking to capture action shots, make sure that there is plenty of room for the dog to run safely. If you are planning on letting your dog off leash, make sure that it is legal and safe to do so. Do not take your dog off leash if there is a chance you may encounter dogs on leash, as that may risk a dangerous altercation as many dogs are leash aggressive. If you’re thinking a location would work if you can quickly leash a dog when threats present themselves (such as the odd passing truck), it’s time to take a step back and rethink shooting at that particular location. It’s simply not worth the risk.

3) Allow the dog to keep running

If you want to capture a dog running at pace, you do not want the dog returning to the photographer’s position. There are few reasons for this. For one thing, you don’t want a frothy dog bounding at your gear at full pace — that’s just asking for gear to break. But more importantly, most dogs will slow as they approach their destination.

Often dropping to a trot or walk well before they reach whoever is calling them. If you want a dog to run at you, it is much better to position someone behind the photographer when recalling the dog. This will increase the amount of time the dog is running at full speed and improve your odds of successfully photographing the dog running.

4) Perspective is the key to effective visual storytelling

Typically when photographing a dog you want to get low and at their level. As the dog is the central character in your visual narrative, you want to capture the scene from their perspective and feature them prominently in your frame. While that is a great general rule to follow, it’s not always your best option. It’s important to consider purpose of your image, specifically what is the mood and idea that you are looking to convey.

If you are photographing a dog running through long grass or boulders you may want to shoot from an even higher vantage point. For example, in the image above we actually took a position directly above the dog and shot down from a cliff face, allowing us to capture the beautiful contrast between the white salt lined boulders and red dirt at the Worm, a famous hiking destination located in the Vermillion Cliffs region of the Utah and Arizona border.

But when photographing the same dog in the nearby hiking hot spot, White Pocket, we photographed the pup from a much lower perspective. This angle allowed us to capture the unusual and almost alien rock formations in the area, focusing on the isolation and wonder presented by the landscape. Likewise you are shooting inside of a forest, often you don’t want to capture the sky, but you do want to lend a sense of scale to the towering trees – so you may want to shoot from a slightly higher perspective.

Even if chasing a dog’s perspective, it’s important to account for sight lines. Take this alternative take from the Vermilion Cliffs National Park session as an example. As we are including the dog within the photo and the dog is looking down to survey the desert landscape, we wouldn’t achieve the dog’s perspective by getting low. Instead, we had to find a much higher vantage point to capture the relative sight line of our subject. By accounting for the dog’s actual perspective our image captured the vision and journey of the pup — rather than focusing on the dog itself.

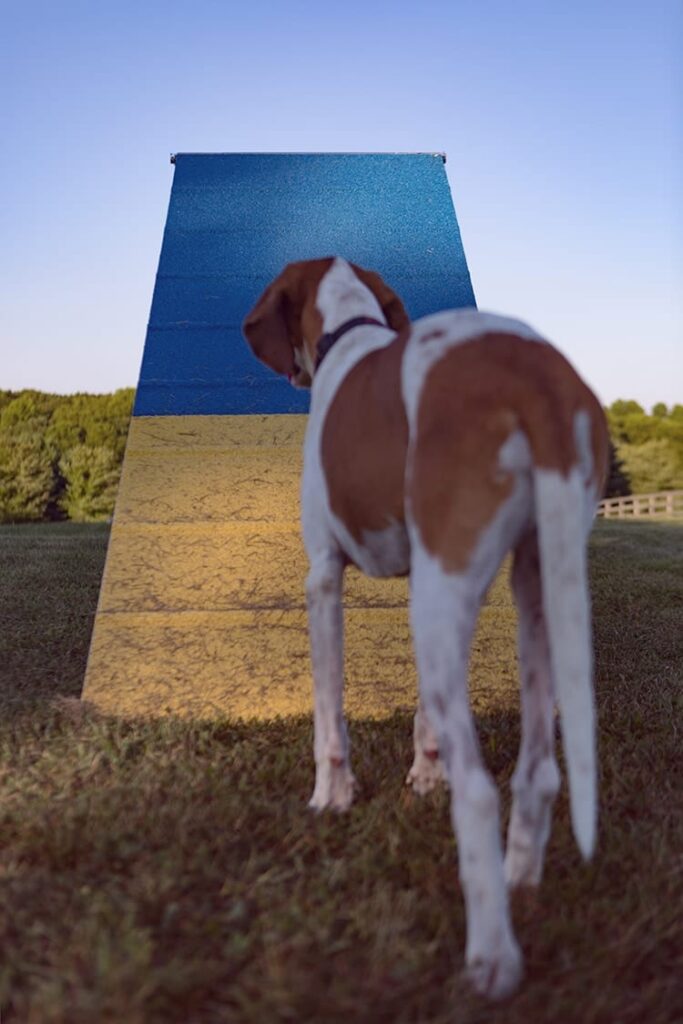

This photo is another great example of using the sight line of a dog to tell a story. Notice in this scene that the camera is actually positioned far lower than the dog’s face, but does not include the dog’s face. While we are including the dog in the frame, our focus is not on the dog, but instead we are focused on the frame. In fact, our exposure (and reflector) are aimed at the top of the frame. While the dog plays an integral role in this story, the narrative central to the image is the obstacle the dog is over coming and not the dog itself. Like most stories, this image doesn’t simply begin and end with a detailing of the character, rather it is engaging because it presents perspective of a journey and the obstacles that (in this case, literally) stand in our protagonist’s way.

5) When composing your frame, set it and forget it

There are a ton of reasons why using a tripod is a good idea. Tripods serve a number of important purposes in photography – including reduce camera shake, make focal compositing possible, make leash removal a much simpler task, and allow for pet photographers to achieve true High Dynamic Range imaging. But more importantly a tripod allows photographers to frame thoughtfully and move on to other tasks that require concentration or active engagement – such as focusing and animal handling.

Dogs can be fairly unpredictable, so your first instinct may be to chase them with your lens. But while dogs do tend to be unpredictable, they’re a variable – a manageable one, at that. But elements that may ruin a frame (such as background clutter or glare) and elements that may improve an image by lending a sense of scale or time (such as landmarks, sunsets, and other scenery features) all tend to be relatively static or are at least predictable. By composing your frame with a tripod you’re effectively locking in the elements of your frame that will not move. This frees you to focus on managing one variable (the dog) rather than balancing a dozen elements simultaneously.

6) Concentrate on where the dog is going, not where it is

Another benefit of locking down your compositional layout with a tripod is that it allows you to be mindful of how the dog is included within your frame. Regardless of how you compose your image, be it through use of leading lines, the Rule of Thirds, the Golden Ratio, or any other compositional method, there are only a few places in your image that the dog can be optimally positioned. If you’re photographing the dog in a seated or other static pose, you can literally just move a dog to this spot and tell it to stay (assuming it knows the Stay command).

When photographing a running dog, things get a little more complicated — as it’s impossible to run and sit still simultaneously. But by guiding a pup from one spot to another, and ensuring that your optimal compositional position is between these two points, it’s really not that difficult to get a dog where it needs to be. It might take you a few tries, but it is a surprisingly viable approach that many pet photographers simply over look.

7) Use predictive focus techniques

Do not use Auto Focus when photographing dogs. Many photography blogs suggest using auto focus and focus tracking. The reason for this is because they confuse pet photography with wildlife photography and sports photography. Which in a way is a fairly reasonable assumption, as dogs are animals and run like athletes. But what these photo experts are forgetting is that both wildlife photography and sports photography are predominately passive affairs. Meaning, they are capturing events and documenting scenes as they unfold. Where as a good dog photographer generally takes a more active approach towards photography and will actually create scenes.

Pet Portrait Photography and Wild Life Photography are NOT the same thing

The reason for this disparity is fairly simple when you think about it. Dogs, by and large, listen to commands. If a pet photographer misses a shot, they can have a dog rerun the same route over and over again. But if you’re photographing a football game and you miss the big play, no amount of begging or treats are going to convince the teams to rerun the play. You either got the shot or you didn’t. Autofocus provides this safety net, but does so at the cost of giving up some creative control. Autofocus will ensure that part of your dog is in focus – but what part? A dog’s eyes are typically on a different focal plane from their paws or nose (which would be the closest body part). So, even if your camera’s autofocus mechanism is working flawlessly it is still likely to produce an unacceptably soft image in more extreme apertures when printed in larger formats.

What is predictive focusing?

If you are building frames as we outlined above in steps (5 & 6) there is an alternative – predictive focusing. With the predictive focus methods you manually set your focal point at an assumed position. In other words, you are focusing on where the dog will be, rather than tracking it as it moves. While this technique might sound a little haphazard and lot like you’re just guessing, but in all actuality the opposite is true. If you are composing your frames thoughtfully, you should already know where your subject needs to be positioned to capture that perfect shot.

Many aspiring pet photographers have a difficult time focusing on running dogs simply because they don’t trust their framing skills or they forget they’re not shooting video. If you are shooting stills, it is important to remember that you are only looking to capture the tiniest fraction of a second of the action. The dog does not to be in focus the entire time the dog is in frame. The dog only needs to be in focus when you are closing the shutter. So, why bother focusing elsewhere? Figure out where you know the dog will be, find an element of the frame at an identical distance or use a stand in (I’ll often have the dog’s owner hold their hand out where I know the dog will be), turn on live view mode, and then zoom in on that exact point to focus.

The predictive focusing technique isn’t entirely foolproof (neither is autofocus) and requires a photographer to have fairly keen eyesight. But those pet photographers willing to take the time to master this advanced focusing technique will find that they will produce far crisper and more interesting photos more consistently than those photographers entirely dependent on autofocus.

Focal distances are impacted by direction and distance from the frame’s center

For most DSLR lenses, focal planes are determined by the subject’s distance from the lens, also know as a focal distance. When considering this concept it is important to remember that you’re measuring distance between two point in 3D space and not measuring distance along a single vector, like hashmarks on an American Football field. This means when focusing on a running dog that you have to consider both the path and stride of the dog through the frame.

How do you focus on a dog running laterally across your frame?

Just like a stopped clock, a dog that crosses your frame (assuming you are absolutely centered) moving directly from left to right will be at the same focal distance twice as it crosses the frame. The dog will start at the same focal distance and end at the same focal distance. As the dog approaches the center of the frame, it will be relatively closer to the camera, and as the dog exits the frame it will be relatively further away. Practically speaking, this means that your effective focal distance shouldn’t change all that much towards the center of your frame.

How do you focus on a dog running towards the camera?

Capturing sharp images of dogs running towards the camera is generally one of the more difficult shots to nail down. There are a few reasons for this. As you may have guessed from reading the last description, a dog that is running towards the camera will be breaking increasingly closer focal planes. But depending on the length of your lens, the focal distance will not likely approach at what is perceived at a consistent rate – even if the dog’s actual speed remains constant. Moreover, the vast majority of non-shepherding dog breeds tend to leap and bound when running, which will incrementally change their height as they approach the camera. Be sure to account for your dog’s stride when focusing.

How do you focus on a dog running diagonally across your frame?

Tracking a dog that is running diagonally is simultaneously both easier and more difficult than either lateral or direct paths depending on their heading and where you wish to capture the dog in the frame. If your dog is running away from the front of the scene, changes in your focal distance will be somewhat mitigated as they move towards the center of the frame, but changes in focal distance will be amplified as they move towards the edge of the frame. The inverse holds true if you dog is running towards the camera. Focal distance will increase rapidly as the dog approaches the center of the frame and then changes in focal distance will diminish in magnitude as the dog moves further from center.

8) Be mindful of the limitations of natural light

If you are photographing running dogs outside you will be doing so with the help of the Sun. While natural light can be wonderful to work with, it can also be fairly brutal. The best natural light is generally found in more diffused situations, typically when it it is cloudy or the sun is nearing the horizon. This means that the best natural light occurs when it is the most fleeting and will change the most dramatically. So, when working with decent natural light means that you are inherently working on a tight and limited deadline.

When scouting it is best to visit your location around the same time of day when you expect to shoot. Taller structures, trees, even mountains that seem irrelevant during the afternoon might throw shade later in the day. But by visiting your location prior and at the right time, any of these issues should be immediately evident even upon casual inspection.

9) Enhance natural light with a reflector

Rarely is natural light optimal. Shooting during the middle of the day (especially in clear weather conditions) may result in unacceptably harsh shadows. As seen in the example photo above, bouncing sunlight into these shadows with the help of a handheld reflector can soften shadows dramatically and lend a pleasant texture to your dog’s portrait. While you might see softer shadows in more diffused lighting conditions, you may find that the light is simply not bright enough to use faster camera settings. But my aiming a reflector at your pup, you can help amplify the available light and in turn, enhance your exposure without compromising lens or shutter speed — as unlike strobes or flashes, reflectors do not have maximum sync speeds.

When to use Silver photography reflectors

There are a few situations that you will want to use a silver reflector, rather than an opaque white reflector.

Low light environments

When you absolutely need to maximize the amount of light that reaches your subject, use a silver reflector. Silver reflectors allow bounced light to take a much more direct path than white paneled reflectors. According to the Inverse Rule of Squares, light is half as bright at twice the distance. Meaning, the more direct a path light takes, the stronger it will likely be.

Diffused natural light

When photographing dogs on cloudy and overcast days, natural light is commonly heavily diffused. As this means that the light you are bouncing with your reflector is coming from a less direct source or direction, it is often safe to use a silver reflector without risking specular hot spots.

Twilight / Dusk / Dawn

Early and late day natural light can present some pretty amazing colors, presenting bright swaths of violet, crimson, golden and cyan hues. Using a silver reflector, particularly one with a more specular or reflective texture, will make it easier to reflect these hues back at your subject.

Photographing black dogs

When working with dogs that have purely black coats, it is often easier to capture the sheen on their coats rather than expose to their fur. Side lighting your dog with a silver reflector will often help bring out this shine and enhance snout and face details on darker furred dogs. For more tips, visit our How to Photograph Black Dogs photo guide.

When to use White photography reflectors

Soften harsh shadows

When photographing dogs outside near mid day or during extremely clear conditions you’ll often have plenty of light to work with. But as this light is overhead and not diffused, it tends to generate harsh shadows to your frame. These shadows may obscure details, set an unfortunate mood or tone, or simply make it impossible to properly expose your frame – simultaneously underexposing and overexposing the image. But by reflecting light into shadows with a white reflector, you can help soften sudden spikes in contrast and brighten darker aspects of your subject to a more perceptible level.

White / lighter fur dogs

The biggest issue that photographers face when working with white dogs is that their fur tends to outshine anything else in the frame. This means that their noses and eyes will likely be wildly underexposed in comparison to the rest of their body. A white reflector can help lend a soft glow to these darker facial features. Allowing photographers to set their cameras to faster settings, pulling back whites to more reasonable exposure levels and help freeze the action even further.

10) Hide artificial light sources in your scene

If you are working in darker conditions or more shaded scenes (in a forest with a thick overhead canopy of leaves), there may simply not be enough natural light to work with — even if you use a reflector. In these situations it can be tremendously helpful to hide a battery powered radio triggered artificial light source (such as a flash, strobe or monolight) within your scene. This is another benefit of building a composed frame, versus passively capturing a scene. If you know where a dog will run and you know where it needs to be within your composition, all that is left to do is light where the dog will be.

Portable flashes and monolights, are built with increasingly smaller footprints seemingly every year. Just toss on a small soft box or octobox, hide the flash behind a bush, thicket of grass, or stump. This will allow you to freeze the action with soft quality light without anyone else being the wiser that you “cheated”. And no, photographing dogs with flash is not especially dangerous. In fact, most vets agree that flash is far less harmful to dogs than natural light.

Flash is often limited by maximum synch speeds

It is important to keep in mind how fast dogs can run when photographing action shots. Most dogs run at a pace that exceeds the 1/200 sync speed cap of most radio controlled camera flash devices. You may capture a decent image at that speed. But with a faster shutter speed and you’re likely to over shoot your camera’s max sync speed, which will result in your 2nd shutter leaving shadows in the bottom of your frame. And, if the dog you are photographing is exceptionally quick your photos may not be as crisp or sharp as you would otherwise wish.

High-Speed Sync helps – and is surprisingly affordable

If your camera supports high-speed sync you may be able to push those settings a great deal further. In fact, some modern monolights, such as the Godox AD600BM, may help your camera reach flash sync speeds as high as 1/8,000 of a second – which is plenty fast to free most action shots and stop any dog in its tracks. Priced at just over $500, these devices are not cheap. But in actuality are not priced much higher than prosumer SpeedLites and will set you back less than upgrading to a faster telephoto zoom lens (as outlined above).

11) Use a Treat and Train

Remote reward dog train devices can be an absolute life saver when photographing running dogs with a skeleton crew. We learned about these devices from one of our pet portrait clients that agility trains Foxhounds. When we saw it in action is absolutely blew our minds. The idea is simple. You load the battery powered station up with training treats and then walk away. When you’re ready to motivate your dog to action, simply activate the hand held remote and the device will let out an audible chime and release a treat. As the device is a novel stimuli and reliably distributes high reward treats, even the slowest dogs tend to pickup on how they work rather quickly.

These devices work from up to 100 feet away and operate on 4 separate remote channels – meaning you can use multiple devices simultaneously and encourage your dog to run back and forth without any further assistance. Great if you are a DIY photographer working with your own dog or an aspiring professional pet photographer who can’t yet afford an assistant. But considering the device’s small profile, which makes them easy to hide in the frame and low cost (at the time of this article Amazon is selling the devices for only $150 with free Prime shipping), this a tool all pro pet photographers should probably keep in their kit bag for on location shoots.

12) Use a telephoto lens

Long-focus lenses have a focal length that is longer than the diagonal width of the camera’s sensor. In the modern digital photography area most long lenses that you will find compatible with your DSLR are labeled as telephoto lenses. This label refers to a specific type on long-focus lens that uses a specific internal lens group that allows the lens to be physically shorter than the focal length of the lens. If you’ve ever picked up a 200mm lens and wondered why it wasn’t actually 200mm long, that’s why.

What is the best lens for dog photography?

A telephoto lens offers a few benefits when photographing running dogs. These long lenses compress backgrounds – making far objects appear closer and narrowing the camera’s field of view. Practically speaking, this will make notable frame elements such as landmarks, monuments, and other landscape features appear closer. While making it easier for you to compose frames free of background clutter. Longer lenses also have the added benefit of providing a narrower depth of field.

While this will make keeping your fast moving pup in focus a bit more difficult, it also means that if you nail the focus that dog will stand out more clearly from the background. Effectively softening and flattening your background while simultaneously lending your subject a pronounced almost 3D look and feel. That said, if you are photographing dogs in more controlled studio environments or need to remain closer to your pup when shooting, you will have much better luck with a wider lens.

13) Use a zoom lens

Zoom lens can be used at different focal lengths. A telephoto zoom combines the best of both worlds — they’re long, relatively compact and provide the perspective of multiple focal lengths. Zoom lenses also tend to provide a substantial cost savings. While a zoom lens compared to a single prime lens might be a bit more expensive. If you compared the cost of a zoom lens versus the cost of acquiring all of the equivalent prime lenses a single zoom lens can cover, the cost comparison is rather striking.

Telephoto zoom lenses make photographing running dogs easier

There are a few reasons why you want to use a zoom lens when photographing running dogs. Simply put, a decent zoom lens will save you time in the field, will take up less room in your kit bag, and will provide you with a wider selection of focal lengths than primes alone. And as a zoom will force you to change lenses less often, it has the added benefit of making it less likely that you will get wayward dust, dirt, fur or other particles on your sensor.

What is the best lens for photographing running dogs?

Telephoto zoom lenses can get pretty pricey. While there are many valid arguments for using more expensive lenses that offer faster f-stops, image stabilization (IS), advanced lens coatings and longer focal ranges, the vast majority of pet photographers can get by without the help of these bells and whistles. For aspiring pet photographers that are Canon users, we highly recommend the older model Canon EF 70-200 mm f/4 L telephoto zoom lens. This lens can produce beautiful images in the most commonly used focal lengths and aperture speeds used when photographing action shots of dogs. And, as this lens is priced at only $600 new, you can pick up this great lens for $1,400 less than Canon’s updated Mark III f/2.8L lens equivalent.

Spend the savings on other gear – such as tripods, lights, stands, and reflectors

While the newer lens is unquestionably better than the older model, most newer photographers will likely find the savings better spent on other gear that will make a much more significant impact on the quality of their photos. If you’re planning on using a solid tripod or monopod you won’t benefit much (if at all) from IS. While having a faster lens can be handy in some low light conditions, the depth of field provided by a long lens at f2.8 is likely to narrow to be practical when photographing running dogs.

Instead, spend the savings on a decent monolight, light modifiers, stands, and reflectors. You’ll capture a wider range of better photos with this gear and more importantly, make your sessions much easier on yourself.

13) Use fast camera settings

As a general rule of thumb you want to prioritize your camera settings in the following order: shutter speed, aperture, ISO. This approach will lend you a general ball park of acceptable image quality. To fine tune your image quality, run through this pattern in reverse — capping ISO as needed, tweaking your aperture width and then adjusting shutter speed to

Shutter Speed

As running dogs tend to be fast moving, you need a fast shutter speed to freeze the action and keep your subject from appearing blurry. Generally speaking you want to use the fastest shutter speed possible, without noticeably compromising your aperture or ISO. If you are photographing a dog you at minimum a shutter speed of 1/200s. To photograph a running dog, you will likely require a minimum shutter speed of at least 1/800 or faster.

Apertures

A wide aperture (designated by a low f-stop) will help increase the amount of light that is allowed to enter the lens at any given point in time. Aperture width is limited by your lens, with “faster lenses” being those that allow for wider apertures. Note that wider apertures have narrower depth of field. If you open your lens all the way up you may not be able capture all of a dog’s face without part of it appearing unacceptably soft, fuzzy, and out of focus.

Narrow apertures and higher f-stops have their own issues, in that they make lens aberration more prominent, but you are unlikely to experience this issue photographing a moving dog. Most lenses are their sharpest in the f5.6 – f10 range. But to photograph a running dog you will likely want to use a much faster lens setting, f1.8 – f4 depending on the situation.

ISO

When you increase your ISO you are essentially increasing the sensitivity of your sensor by grouping more pixels together to capture more light. More sensitive sensors require less light to achieve the same effective exposure — which is a good thing. But increasing your ISO also increases the amount of noise that you are introducing to each frame. Which makes sense when you think about why the sensor is more sensitive. When you merge multiple pixels together you’re effectively averaging all of the info from those pixels together into a single value. The more pixels that you are averaging, the less likely it will blend smoothly with its neighboring pixels.

What is considered an acceptable level of noise to introduce via ISO depends primarily on the taste of the user and how you intend to use the photos. Noise tends to be more noticeable in larger prints and as our studio primarily produces larger format prints, we very rarely ever exceed 800 ISO and almost always stick to 100 ISO when working in studio.

That said, to capture the featured image for this post (the first one) we actually went up to 3,200 ISO. Something we don’t normally do, but again, when working in relatively low light conditions, like later twilight, sometimes compromises have to be made.

14) Approach your session with a solutions based mindset.

The best way to improve is to fail quickly and fail often. By all means celebrate your successes. If you see that a particular aspect of your shoot is going well, double down on it. But it is important to remain actively critical of your photos at all times — especially during your shoot. Meaning, don’t be afraid to stop occasionally for a brief image review, find things that aren’t 100%, and look for ways to improve. A good photographer might “get the shot” within a few minutes. But great photographers push beyond “good enough” and strive to capture truly excellent and inspired images.

This is an especially handy mindset to maintain when things go wrong. When the unexpected happens, focus on what is ruining your shot and how it is specifically impacting your workflow. Often times critical failure points can be over come with relatively simple solutions if you can break your issue down into a simple identifiable problem. Remember, even if you can’t capture the exact shot you want, the introduction of this new dynamic might provide a creative opportunity you never would have discovered if conditions were optimal. In short, remain flexible and open to inspiration whenever it presents itself.

15) Practice. Practice. Practice.

Practice won’t make you perfect. But it will make you better. The better you know your camera, the quicker you will be able to adapt on the fly and capture events as they present themselves. More importantly, repetition is one of the fastest and easiest ways to boost your situational awareness.

While it is impossible to ever truly multi task (humans can only really concentrate on a single task at a time), with enough practice you can learn to perform simpler tasks with little to no concentration — making it much easier to jump from task to task quickly and reliably.

More importantly, the more experience that you have completing different types of shoots, the faster you will pickup on potential headaches before they occur and the more readily prepared you will be to handle (if not out right prevent) the unexpected.

Photograph running dogs like a pro

Photographing running dogs and actions shots of pups really isn’t all that difficult with the correct approach. You just need to make sure that your pup is properly lit and framed, that the shutter speed and lens is fast enough, and that your dog’s face remains in focus. While that may sound like a mouthful, when you think about it that’s really only four things. As long as you take a solutions based approach to your shoots and continue to practice you will be photographing running dogs like the a professional pet photographer in no time!

The Puptrait Studio may collect a share of sales or other compensation from the links on this page. Prices are accurate and items in stock as of time of publication.

About the author: J.B. Shepard, is a professional pet photographer, dog advocate, and founder of the Puptrait Studio. J.B. lives in Hampden, with his wife and two dogs — George (a Boggle) and Lucky (Jack Russell Terrier).